A visit to the European Southern Observatory

At the edge of the Atacama desert, not far from Antofagasta, sits the European South Observatory. It stands in the so called “telescope alley” full of various nations’ optical and radio telescopes. In fact, near San Pedro, the ALMA radio telescope is the most expensive terrestrial telescope ever constructed. What the instruments positioned atop Mauna Kea in Hawaii do for the northern hemisphere, the Chilean ones do for the southern one, as some sections of the celestial sphere are visible only from south of the equator.

Perched on top of the Cerro Paranal, fast flowing Humboldt current running north along the coast of South America creates a temperature inversion, reducing cloud cover, and further benefitting from the dry, arid air of the Atacama desert. The elevation of the station adds to its propitiousness, lifting it up over morning fog and the thicker air—perhaps being closer to the heavens.

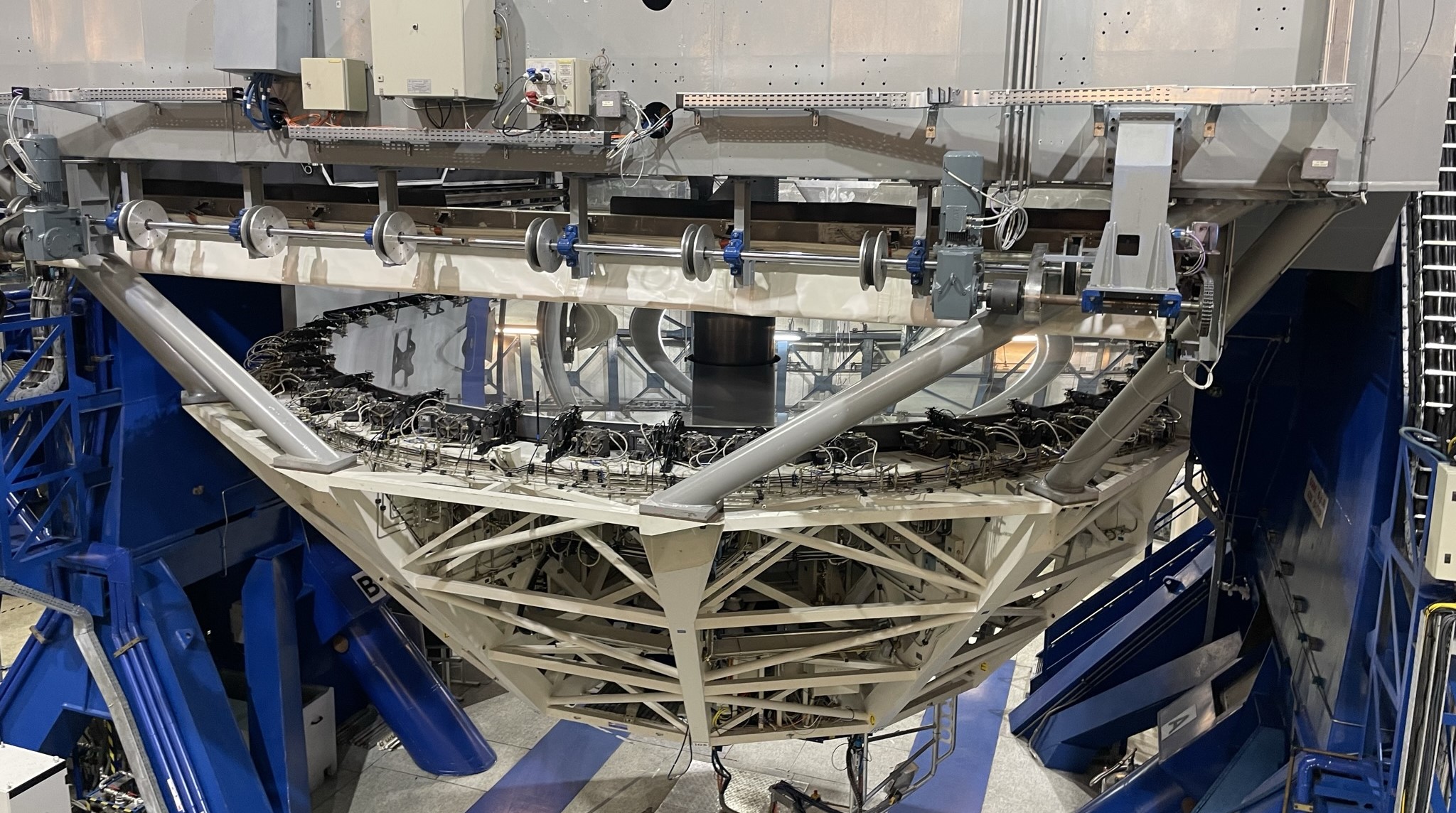

But while surrounded by timeless dusty red sandstone, and hundreds of miles of featureless desert, inside we find something which is the pinnacle of human engineering. The heart of this instrument is an 8-metre reflective mirror, taking 8 years to construct in Germany, before being shipped to France for its microscopic aluminum surface. It has tolerances in the nanometer range in order to create a perfect parabola. It captures the feeblest rays of distant starlight which, after travelling wearily for millions of years, fall in exhaustion on the mirror. For an hour or more, the mirror lovingly gathers that light—4 billion times fainter than the naked eye can see—shepherding and concentrating it onto a secondary mirror that focuses it into a recognizable image.

Aside from the mirror, there is a vast machinery, without which the vast, flawless mirror would be useless. Great bearings magnetically and magically levitate the whole of the telescope. No physical bearings are present. So frictionless is the system that, if allowed, a single human hand could move the tons of machinery to aim it. The secondary mirrors that gather light from the large mirror are trained to emulate and dance to the currents of air above the telescope in perfect synchrony, eliminating the apparent shimmering of stars that would reduce the accuracy of the images. No astronomer will soundlessly murmur “twinkle, twinkle little star,” because elaborate systems and electronics eliminate it.

There is a certain silence about this mountaintop, bathed in sunshine from the eternally sunny skies. While the mechanism is silently whirring away, engaged in its esoteric business, the surrounding desert is soundless and timeless, with no plants, leaves or twigs to stir in the breeze, or animals to break the horizon.

While a marvel of engineering, the telescope is also a marvel of international cooperation. Fourteen nations, as disparate as the Czech Republic, Portugal and Finland collaborated to create it. These same nations could never agree on things like commerce, but the great enterprise of science has brought them together. But the consortium invites astronomers from any nation, whether a contributor or not, to use it at no cost. First, they must make a proposal describing how they will use this remarkable, intricate instrument. Then they may receive permission, for three nights, booked two years in advance. Once they collect their data they must publish, within a year, any findings, not only to show that the use of the telescope was not frivolous, but to ensure that the data they collect is open to the entire world, that we might collaborate, and collectively march toward a better understanding of the universe.

Perhaps the most moving aspect of this structure is that it serves only one purpose, the noblest one, of advancing human knowledge. This facility, costing billions, serves no commercial purpose, produces no “useful” products, generates no services (outside of its not insignificant staff of technicians, maintenance workers, chefs, housecleaning staff, engineers and a myriad of others). The machine is a physical manifestation of our loftiest goals: to unravel the mysteries of the wide and wonderful universe we live in. When we wonder about the effort to create the pyramids in Egypt or Mesoamerica, and wonder what their purpose was, it does not differ from this fantastically complex mechanism, poised on top of a lonely and windswept mountain, in a desert in South America. If a distant alien archaeologist comes to earth after the demise of humankind, and finds the ruins of this telescope, they will, I hope, reflect that ours was a race that used its highest technological know-how to build this intricate device to probe deeply into the universe and ponder its secrets.

One Response

There’s a quiet intensity to this piece that makes it unforgettable. It’s the kind of writing that lingers in your mind long after you’ve put the book down or closed the screen. Every line seems to carry with it an echo — a subtle reverberation that invites further reflection, and that’s a quality not easily found in modern writing.